A memoir by Brother Martín Digilio, General Councillor, on the closeness, witness and legacy of Pope Francis, from his days as Cardinal in Buenos Aires to his time in Rome.

It was 2001 when I moved to the city of Buenos Aires. The situation in the country was very complex: the instability of the government and the economy had a great impact on the poorest people. That year I started my service of leadership in the District of Argentina-Paraguay at the age of 35. I had everything to learn and no time to do it.

Among other matters I had to attend to was the transition of Colegio La Salle de Flores, where we had been present for almost 100 years. The Ladies’ Association of the parish of San José de Flores had decided to terminate its legal entity and pass the assets of that society to the Archbishopric of Buenos Aires. My predecessors had begun talks in the mid-1990s; it fell to me to define this together with the delegates of the then Archbishop of the city, Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio.

Between 2001 and 2013 I lived in Buenos Aires: seven years as Visitor of the District and six as Director of Colegio De La Salle. In those 12 years I went to see the Cardinal many times: to resolve matters, to let him know about others. We went through many different circumstances which today, looked at from a distance, are simply anecdotes of no great importance, although at the time they were painful or incomprehensible.

Our concern for Flores was a small thing compared to those he bore: he was actively collaborating with the Argentinian dialogue after the 2001 crisis, in a country in ruins. There were signs of disintegration such as the printing of “quasi-currencies” and debt cancellation bonds circulating as banknotes. There were kidnappings, looting of supermarkets, demonstrations calling for “everyone to leave”. Bergoglio, from the shadows, was a key player in helping Argentina take steps towards reconstruction, always from the perspective of the most impoverished.

In the midst of that crisis, we also acted. We created the Escuela Malvinas, free and popular, in a forgotten neighbourhood of Córdoba. In those days, schools in general, and those serving the most vulnerable populations in particular, were the only institutions that did not collapse. In the meantime, pastoral ecclesiology was resolved as best we could: with pragmatism and great charity.

The years between 2001 and 2013 were a roller coaster: some springs, few summers, and a lot of social division. The provocations, the hatred cultivated in society, left us at loggerheads between families, friends and colleagues. Deep pains were covered up by a frivolity that never knew how to put the vulnerable at the centre. And among the few prophets left standing, there was him.

Many myths were woven around Bergoglio: that he was a Peronist, that he was a politician in the shadows, that he made pacts with the powers that be. But his homilies, his priorities, his way of being with priests and people told another story: that of the Gospel made flesh. And with that he was everywhere.

And now, with his departure, everything takes on another dimension. His death is not just that of a pontiff. It is the end of a period that took the Gospel to the streets, with his shoes full of dust and his heart always pointing to the periphery.

His time in Rome never took him far from the South. He delivered that way of looking at the world from below, from within, from close up; from the back bench, from where those who do not raise their hands are. It was uncomfortable, yes, because he was not looking for approval. He was looking for justice. And tenderness.

In 2008, when the District was beginning a difficult process with the Colegio de Buenos Aires, Bergoglio called the Visitor and the Bursar to give them his support. Discreetly. In 2011, when consulted about a complicated chaplain, he understood instantly, and sent us another one. He described him in two words, counting them on his fingers: “He is a man and he is poor”. Two essential virtues, according to him.

He was not looking for soldiers or bureaucrats. He wanted humanity and simplicity. His authority did not come from the headlines: it came from a deeper, quieter place. Like someone who wields real power when there are no witnesses, when only good matters.

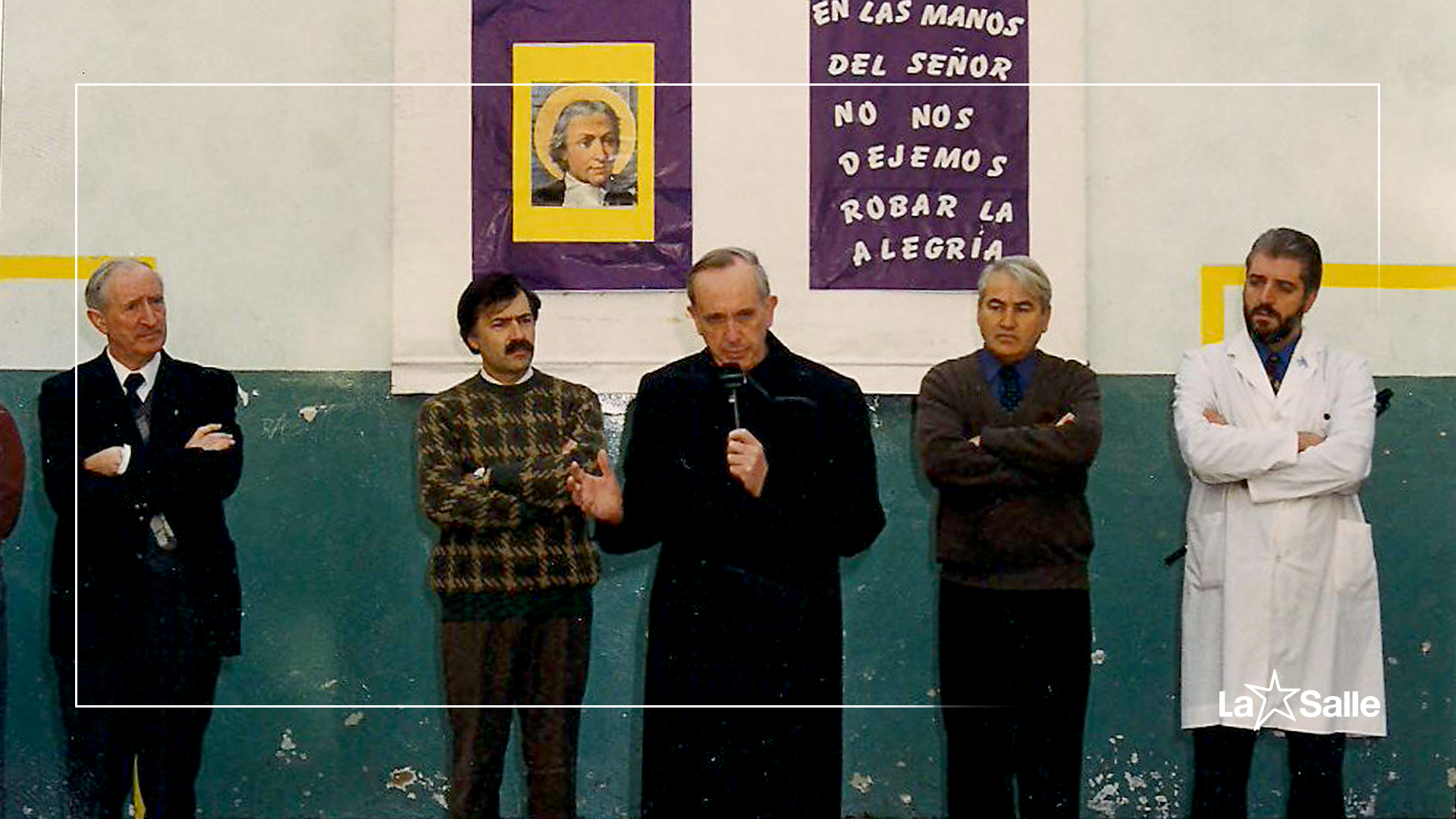

In 2010, during a teachers’ strike, we proposed a day of reflection. We did it with a homily of his on the beatitudes. He gave hints of his vision of the country: inequality, the need for daily austerity, justice for all, fraternity, and a look at the saving sacrifice of Jesus. He spoke of drugs, trafficking, sweatshops, corruption. And never to make the front page of the newspaper.

On 13 March 2013, at a meeting of the RELAL Visitors’ Conference, I remember betting that if the Pope was Latin American, the compatriot would pay for dinner. I lost. I still owe that dinner. I never thought it would be him. But soon the gestures showed where his Pontificate would go. His magisterium – Evangelii Gaudium, Laudato si’, Fratelli tutti – led the way. He helped us to see what no one wanted to see: migrants, indigenous peoples, the disabled, the lonely elderly, children used for war or labour, the discarded.

He taught us that the Church is not a museum of the perfect, but the home of sinners. And he warned us against clericalism, proposing synodality as an antidote. He did not invent anything new: he took the Gospel of Jesus and walked. As in Buenos Aires, but now with the whole world in his heart.

He also spoke out forcefully against abuse by members of the clergy. His fight against paedophiles was firm and sustained, with concrete and painful but necessary measures to restore trust and heal deep wounds. He promoted a culture of protection and justice, ensuring that the pain of victims was not silenced or relegated to the background.

He also insisted on the need for financial transparency in the Church, an institution often singled out for its administrative shadows. He operated for a more austere, ethical and clear management, knowing that witness also depends on how the goods that belong to all are administered.

And at all times, he revalued the role of women in the Church, not as a symbolic gesture but as a profound conviction. He listened to their voices, promoted their presence in decision-making spaces, and openly questioned the structures that make their contribution invisible.

In 2004, in the midst of the conflict over the Colegio de Flores, a group of former students made an attack on the Cardinal. They published an insulting petition. I asked for an audience and he received me. I asked for forgiveness. He grabbed my hand and said: “thank you”. And then we began to look for the best way out. In that conversation he said to me: “Brother, you have to put your troops in order”. And I replied: “and you have to sort yours out”. He smiled.

Since then, “putting the troops in order” has become a phrase among us. A code. A way of understanding that to lead is to take care. That sometimes you have to order, but not to control: so as not to lose anyone. He was also doing the same. With his troops. With the country.

At the 46th General Chapter, he told us that the two great challenges of humanity – education and fraternity – were also ours. That as Brothers we should bear witness to them with our lives. And his teaching had a profound influence on the Chapter. It inspired the Leavening Movement, our revision of structures, our renewed charism.

A few days ago, we went to say goodbye. Once again, we were surprised by the affection of the people. We asked him to intercede: for the suffering children, for the mothers without answers, for the invisible peoples, for the discarded, for us, the educators.

He leaves us a decentred Church. A tenderness that resists. A faith with mud. And a call: to continue walking, with the Gospel in our backpacks, knowing that another world – yes, still – is possible.

And that we still have to settle the troops.

Rome, 25 April 2025

Br. Martín Digilio FSC